Measure the unmeasurable: botnet and German tanks

Disclaimer: Nothing in this blog is related to the author’s day-to-day work. The content is neither affiliated nor sponsored by any companies. The story in this post is NOT based on a true event.

What if there is no ground truth, but we still need to produce a number?

A few months ago, a security researcher friend of mine, let’s call him Jason, shared an exciting update: he partially reverse-engineered a peer-to-peer botnet protocol and planted a few spy nodes into the network to track the botnet!

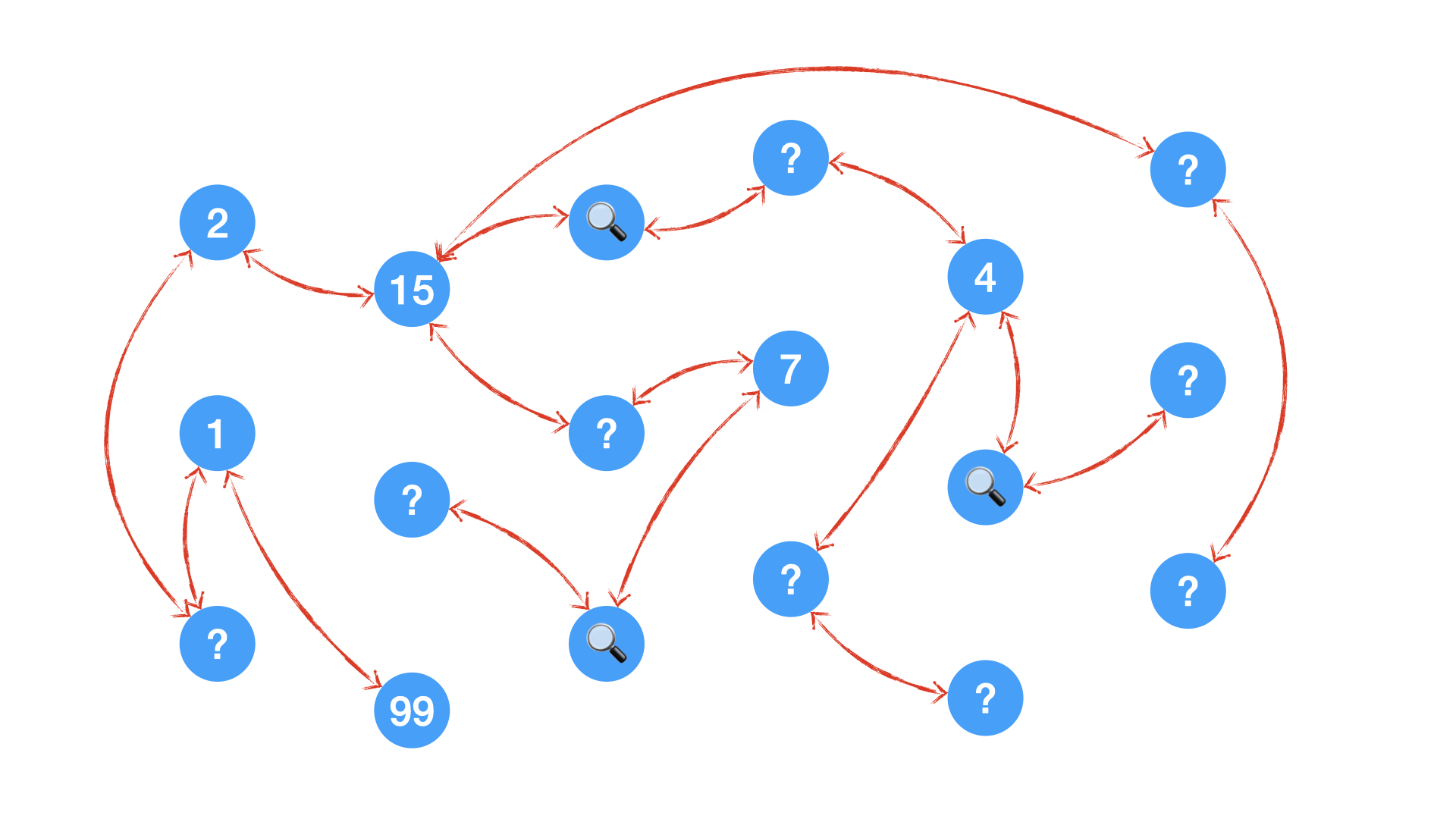

What wonderful news! Just so you know, a peer-to-peer or “p2p” botnet* is a network of compromised and controlled computers, “bots,” that use a p2p structure to be controlled without the need for a centralized command-and-control server. To keep the network active and updated, such botnets usually have their own communication protocol. Jason could forge a few network nodes and monitor the traffic without being noticed by the botnet owner.

However, Jason was unable to determine the size of the botnet or its growth rate, among other things. He couldn’t continue his investigation without such a number. It was because the malware author limited the network connectivity rate so that a node could only discover and connect to a fixed list of randomly assigned nodes, which was later discovered to be caused by a random seed initialization failure in the code. As a result, Jason couldn’t estimate the size of the botnet because he only saw the same list of nodes every day:

1455, 4089, 19234, …., 57899, 69970

“Wait, is it true that each node has a unique numerical ID? I mean, numerical!”, I said.

“Yes, the disassembled code can confirm, but only the bot itself can know its own ID when initialize and we don’t know how fast it can grow, plus the node assignment algorithm takes MOD to a prime number …” Jason said.

“Sorry for interrupting but I might have a brilliant idea. Can you plant a few more of your spy nodes in the botnet and confirm if new nodes IDs are always larger than the old ones?” I said.

A few days later.

“Yes, all new nodes can have larger numerical IDs than before, so?” Jason said.

“Have you heard of German Tank Problem *?” I said, “Let’s get back in 1944.”

Before D-Day in WWII, the US Army needed to estimate the number of Panzer V tanks to be used, but the Allies only had a few serial numbers of captured or destroyed tanks, so mathematicians devised an estimation method. The approximated median can be used to estimate the number of tanks:

\[\widehat{N} = \frac{k+1}{k}m -1 = m + \frac{m}{k} -1\]where $m$ is the largest series number and $k$ is the sample size. It can be understood in this way:

There must be more tanks produced later the largest series number one, but how many more? If we knew all series numbers ($m$=$k$), $m$ is the number of tanks and no more tank after number $m$. Since we randomly sample in the series number, we could have missed a gap of series number because $k$ was smaller than $m$, and $m/k$ can be a good (unbiased) guess of expectation so we need to add it back. Why minus one? Well, it can be as simple as reduction when $m=k$ so $\widehat{N} = m$, but the true reason comes from the argument between frequentist and Bayesian, please read further and find out. Such method, called Minimum-Variance Unbiased Estimator (MVUE), could accurately estimate the population size with very limited sampling. Most important, the sampling in the sequence didn’t have to be uniform.

We were now in the year 2022. Jason had the largest botnet ID of $223779$ with $200$ sampling points when all his forged nodes and communicated nodes were added together, so the approximate size of this p2p botnet was:

\[\widehat{N} = m + \frac{m}{k} -1 = 223779 + \frac{223779}{200}-1 = 224897\]Two days later, Jason found his newly deployed nodes reached ID $557303$ with $250$ sampling points, so the new size was:

\[\widehat{N} = m + \frac{m}{k} -1 = 557303 + \frac{557303}{250}-1 = 559531\]Jason had both the size and the growth rate of the p2p botnet by simply deploying a few new nodes and collecting the ID numbers, allowing him to understand the exploited vulnerabilities and other factors like geolocation behind the growth, as well as a daily updated dashboard for his senior management.

Why not just use $m$ the largest ID as the population size? $m$ value came from random sampling without knowing if uniform or not so it could be very arbitrary.

Six months later, I received a follow-up message from Jason. He had some ground truth after successfully taking down this botnet and validated each number. They were as precise as the Allies’ estimation of German tanks.

Still a mystery: the attacker used MOD to a large prime number to calculate the neighbor ID, but we were able to estimate it accurately. “The prime number was too large, and the attacker had no idea the botnet would be taken down so quickly before it arrived.” Jason said.

“Do you still want to learn Fermat’s little theorem?” I said.

“Thanks but no need for now.” Jason said.

Certainly, the real-life scenario was not simple. We now know that the sequential pattern was the secret key, but it was hidden in depth with many details, and we couldn’t guarantee that such luck would exist in other botnets, such as if the attacker was good at math and used a hashing function for the bot ID.

My dear readers may want to ask about any other amusing examples of estimation problems in real life. Yes, such measurement for an unmeasurable problem can exist in a coffee shop too. The coffee shop owner can skip a few numbers between two orders to make the revenue look good to investors; however, such a trick can be discovered by the similar method described above, and the coffee shop later on receives a large fine from the SEC*.

Reference

- Peer-to-peer botnet https://www.cs.ucf.edu/~czou/research/P2PBotnets-bookChapter.pdf

- German Tank Problem https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_tank_problem

- Luckin coffee materially overstated its reported revenue https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2020-319